Since the abolition of the mandatory belonging to a students’ union in 2010, the conditions of the students’ influence have been worsening. Among the hardest hit are the full-time remunerated staff of the students’ unions, who bears testimony to an absurd workload and burnouts.

Text by Oliver Hugemark

Translation by Estrid Ericson Borggren

Illustration: Abigail Allen

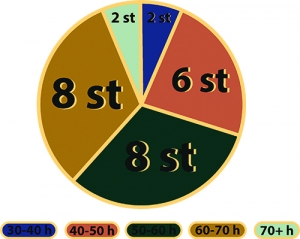

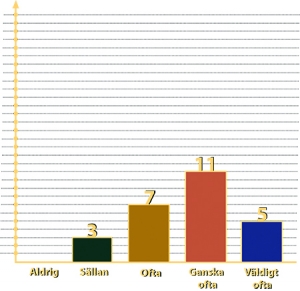

In a survey sent out by Lundagård to examine the work situation for full-timers in Lund’s student life, a majority of the responding full-timers testify about a strained and, in some cases, unsustainable work environment. Of the 26 union full-timers who chose to participate in the survey, 21 feel that the workload is either big or too big, and 23 are often or very often feeling stressed. Only 4 participants state that the workload is just right and 5 that they rarely feel stressed.

“I believe that in student life, in general, there is a situation where being able to work well under pressure has come to define competence and suitability for the job as a full-timer. You must more or less be the one who can do the most and work the longest in order to handle the job”, says Sara Thiringer, currently Vice Chairperson of the Student Union for Social Sciences at Lund University.

To understand how this situation has emerged, we need an overview of the history of the Swedish students’ influence, which stretches itself almost as far back in time as the universities themselves. It was in connection with the creation of the Swedish National Union of Students (SFS), an association of students’ unions at the Swedish universities, in 1921 that the structured students’ influence really took off.

Another milestone for the increased students’ influence was at the end of the 1960s when students in all of Sweden during a few turbulent years loudly voiced demands for a wider influence. In 1977, there was for the first time regulations added to the Higher Education Act, stating the students’ right to actively participate in among other things in board duties at the universities of the country. Since then the student participation at our seats of learning has continued to grow, and the Swedish infrastructure of students’ influence has under a long period been unique and among the foremost and most ambitious in the world.

The 10th of July 2010 was a turning point in the history of students’ influence which eventually led to worse conditions for the students’ influence and tougher work situations for the full-timers at the students’ unions. Then the Swedish Parliament decided to abolish kårobligatoriet, which previously had made it mandatory for all students at Swedish universities to belong to a students’ union. In practice, this meant that the students’ unions could no longer maintain as high membership fees as before. Most students’ unions, who had previously been funded by membership fees, saw fewer and fewer new members, and by that lower income from members, which created a widespread concern for the future of the students’ influence.

After the abolition, the government’s investigators of the issue found that 310 Swedish kronor per student and year were required from the State for maintaining the students’ influence. Despite this, the government chose to only compensate the unions’ loss of income with only 105 Swedish kronor per student and year. Swedish universities soon realised that this was unsustainable and decided to contribute some money of their own. Still, this was not enough to reach the same level of funding as before the abolition of kårobligatoriet.

In March 2017, the Swedish Higher Education Authority (UKÄ) published an extensive report in which the conditions of the students’ influence after the abolition of kårobligatoriet were mapped out and analysed. The report reveals among other things that the majority of the seats of learning in Sweden regrets the underrepresentation of students and means that positions where the students’ perspectives are important remain empty.

As the seats of learning, the students’ unions in the report emphasizes the problems with finding enough student representatives. They also point at an amount of other organisational and financial problems they are facing. In respect to this, the students’ unions highlight the lack of resources for marketing themselves and recruiting and training student representatives. They further say that the offices of the students’ unions today lack sufficient resources for creating and maintaining a network of student representatives.

Jack Senften, former Vice Chairperson of the umbrella organization the Students’ Unions of Lund University (Lus), has read the UKÄ-report and has given several lectures based on it at the university. He agrees that the students’ unions are in need of more money and further means that there are two other important reasons for the lack of engaged students at the students’ unions.

“One reason is that it’s generally difficult for the department boards to find people who want to be engaged. There’s a lack of people everywhere. The other is that all too few students understand what it’s the unions are doing, and what educational surveillance is”, says Jack Senften.

True enough, based on the report UKÄ assesses the one most important measure to establish a fully functioning students’ influence to be higher grants. Concretely it is recommended that the government increase the current state subsidy three- or fourfold. The intention is that this measure will strengthen the unions’ independence from the universities and equalize the financial conditions of the Swedish students’ unions.

The majority of universities and unions in Sweden agreed with UKÄ’s suggested measures. Approximately half of the universities agreed that the students’ unions finances must be strengthened through an increased grant. Among the students’ unions, 68% shared this opinion.

One of those Lundagård has talked with to get a better picture of the reality that the survey and the report are portraying, and how it is reflected among the students’ unions at the university today, is Sara Thiringer, Vice Chairperson of the Student Union for Social Sciences.

While she is showing me around, and excusing the messy and untidy students’ union building, she touches on the subject of the full-timers’ workload.

“To be a full-timer means many meetings and late evenings, to be available for the members almost 24/7, and always have more that needs doing. It’s happened that one has had a breakdown after a particularly heavy week or when something didn’t work out as expected”, says Sara Thiringer.

Last year, when she was a board member of the Student Union for Social Sciences, she was part of a workgroup that investigated the work situation among the unions’ five full-timers.

“We examined what required the most time and energy from our full-timers and put this in relation to the overall purpose of the union as it is stated in our statute. The point was to identify time-consuming work tasks that we actually shouldn’t be spending time on”, says Sara Thiringer when I meet her on the first floor in the unions’ pastoral brick-building.

During the examination process, criticism was raised towards the union’s so-called “Free Store”. It was a time-consuming, non-profit initiative through which the union previously had collected clothes and other belongings that had been left by exchange students, so that next semester they could be offered to new exchange students at a free flea-market.

“This is fundamentally a good thing, but it has very little to do with educational surveillance and creating a solidarity among social sciences students”, says Sara Thiringer with a big smile.

Despite that some superfluous work tasks and areas of responsibility could be identified, and discarded of, most measures were small: such as putting up full curtains to prevent visibility from the outside. Consequently, the structural successes were limited.

“There were many larger issues we couldn’t do anything about, such as the fact that us full-timers don’t have enough time to tutor and coordinate our engaged students out at the departments”, says Sara Thiringer.

After the self-examination of the Students Union of Social Sciences, Sara Thiringer came to the conclusion that the major problem in their situation was the lacking funding of the students’ unions. Her reasoning agrees well with the UKÄ-report.

“We, and many other unions, have big problems with filling the posts there are out at the departments and tutoring the representatives that we do have. In today’s situation, we would need an additional full-timer who worked exclusively with supporting the student counsels that gathers our student representatives. If we had more money we would’ve been able to train a chief responsible per department, to whom the engaged students could turn”, she says.

Sebastian Persson, former Vice Chairperson for Lus, and currently Political Secretary at Lund Municipality, does not believe that the students’ unions would need to hire more full-timers, but that they need to delegate work tasks to active members to a much higher degree.

“I think that the full-timers are doing too much administrative work for them to have the time to properly perform the educational politics-part of the job. It’s so difficult to recruit students that the full-timers are doing way too much”, he says when we meet in his brick-walled basement office.

On the way out of the office Sebastian Persson adds that after the abolition of kårobligatoriet, the students’ unions have needed to focus more and more time and resources on social events.

“In order to be attractive to the members, and keep high membership numbers, the students’ unions have taken on more social engagements than before. In theory, though, it’s completely voluntary for the union to do so”, says Sebastian Persson.

Sara Thiringer at the Student Union for Social Sciences shares the notion that more tasks really should be placed upon the members, but that increased grants are absolutely necessary to increase member activity. As it is today, the union’s full-timers spend a lot of time supporting the closer to 70 student representatives doing educational surveillance at a total of 10 institutions and 2 Centres of Expertise and Research. Student representatives can be found in everything from boards and program management counsels, course syllabus groups, and equal opportunities, groups.

“If we’re expected to appoint student representatives in all preparatory and decision-making bodies at departments and faculties, we need to have sufficient central resources to be able to visit all classes to recruit student representatives and then keep in continuous contact with them, develop their competences, and handle the matters they bring us. As it is today we simply do not have the resources to do this”, says Sara Thiringer.

Towards the end of the interview, she talks about how the female full-timers have even more difficult work situations than their male counterparts, as they often have higher expectations placed on them both from colleagues and union members. She further expresses that this is barely talked about and that fewer women apply to the elected positions for this specific reason.

“It’s not talked about enough that women in positions of power often have worse mental health than men. Before I came to Lund I was a full-timer with Save the Children International’s youth wing. There it was a shared basic outlook on the work environment issues and the gender equality issues, and I think that is missing from the unions”, says Sara Thiringer.

Gunilla Jarlbro, Professor of Media and Communication Studies at Lund University, who together with Mia Marie Hammarlin has written a book about elected women and men in the public spotlight, shares the view that elected women, in general, are disfavoured on their workplaces.

“In the Swedish work life, women are in total on long-term sick leave to a higher degree than men. This is also true for the universities. It can’t be explained purely in medical terms, but it is a result of us still living in old structures where we expect more of women than of me”, says Gunilla Jarlbro.

As Sara Thiringer, Gunilla Jarlbro means that women more often than their male counterparts do the invisible extra work, such as ensuring a pleasant workplace and organising social events.

”To come to grips with this all must put on their gender-glasses and actively talk about these issues within the own organisation, in order not to fall back into gender stereotypes. One must be exact with work descriptions and rotating schedules”, says Gunilla Jarlbro.

Daniel Kraft, current Vice Chairperson at Lus, and former full-timer, at the Student Union for Humanities and Theology (HTS), recognises the reality that Sara Thiringer and Sebastian Persson testify.

”During my time at HTS, I had to fill in at the departments to help the union’s student representatives. I had to deal with department issues and attend department meetings even if I shouldn’t have done it”, he says.

Daniel Kraft, who by the way works up to 80 hours a week, has long felt that the unions’ full-timers are too burdened by time-consuming administrative tasks to care for and develop student-political interests. He regrets that the full-timers are more clerks than politicians, as their assignment foremost is the latter.

”For the student democracy to flourish as a democracy there’s a need of full-timers who can focus on establishing more decisions and encourage a productive education-political dialogue”, says Daniel Kraft.

Illustrations and graphic design: Abigail Allen