Building robots is not a privilege reserved for engineering students at LTH. Lundagård talked to Mia Huovilainen and Theodor Årnfelt to learn how robotics is applied in cognitive science.

Humanoid robots, 3D printers and all kinds of technological components lay scattered in a room at LUX. This might not be in line with people’s idea of a building usually reserved for the humanities. The room is the Cognitive Robotics Lab located on the 4th floor of LUX.

Mia Huovilainen and Theodor Årnfelt are master’s students of cognitive science, a subject which incorporates linguistics, psychology, neuroscience and biology. “We study how people interact in different settings. It could be anything from how people interact with each other, to how people interact with different technical artefacts”, says Mia Huovilainen.

The two students are currently doing a project course in robotics, where they act as research assistants. The project entails building five robots for future research. This technology can be used in exploring human-robot interaction, and how human reflexes can be modelled in robots. The robots will also be available for research at other faculties if needed in the future.

The best part is getting your hands on something, to actually build it.

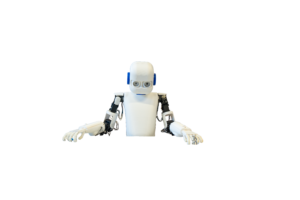

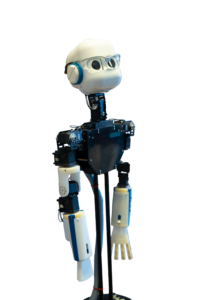

The humanoid robots in the lab are called “Epi”, and do not require any previous experience or programming skills to build. Compared to other humanoid robots, Epi has a simple design yet is well suited for scientists to study development of motoric skills, such as eye-hand coordination, as well as the development of social skills in robotics.

Epi’s overall purpose is to help researchers understand how human brains work. It is not a factory robot that performs certain functions achieved by very goal-oriented programming. Instead, its programming is already built-in, and Epi is designed to be used in experiments in developmental robotics. One of its standout features is the eyes, which have more variability than most interactive robots. “For example, more light makes human pupils smaller. So to have the same effect on a robot, you put different modules or blocks together and integrate them to basically manipulate the size of Epi’s pupils”, Mia Huovilainen explains.

Apart from research purposes, building Epis also gives students experience of working on a real task in a multidisciplinary environment. “The best part is getting your hands on something, to actually build it and see it go from basically nothing to what it is now”, Theodor Årnfelt comments.

In addition to constructing Epis, one of the tasks that Mia Huovilainen and Theodor Årnfelt have is to develop a manual of step-by-step instructions on how to build an Epi, which will be available to anyone who wants to build one in the future. Therefore, they need to document the entire building process. “It has to be accessible to as many people as possible”, Mia Huovilainen tells Lundagård.

She and Theodor Årnfelt started the project from scratch with just the plastic casings that make up the robots’ “skin” . The circuits were later built upon the casings by hand. Currently, having devoted approximately 50 hours to the project, they have finished the torsos of four Epis and started to assemble the eyes. “It was quite slow in the beginning because we were not used to it. We were picking up stuff randomly, and we did not really know what to do with anything. But now we have a plan […] so it sort of sped up as we have gone along”, says Theodor Årnfelt.

The process has not been without trouble. For example, Mia Huovilainen and Theodor Årnfeldt had to redo several zip ties after putting them on in the wrong way, so that they did not work together with other parts of the robot. Apart from that, most things have gone smoothly. They are still waiting for some components to be delivered, so the robots might not be fully done when the course ends.

when the programming in Epi is mature enough to react as smartly as a human being, the robots can be used for studying reflexes. Theodor Årnfelt gives an example “If I try to guide the head of Epi with a gentle push, it means I want it to look over there. But if I do it forcefully, then it is more like an attack. And reflexively, it [Epi, editor’s note] tries to move away.”

The appearance of Epi might be regarded as quite adorable – especially compared to another robot model in the lab with a more human-like face. Mia Huovilainen elaborates, “this is another aspect of interaction research, how to make the robot look as friendly and trustworthy as possible. Because if you interact with the one [with a more human-like face, editor’s note], you would be scared. Most people would probably be very scared.”

When asked about what made them choose this project, the two students share a similar view; the practical nature of the project attracts them. “I think that this programme is very theoretical, and I wanted to do something practical. This seemed like a pretty good fit”, Theodor Årnfelt says. Mia Huovilainen agrees: “I really appreciate this project because most people [in our programme, editor’s note] have done literature studies or data analysis. It’s nice to get a break from reading or sitting in front of your computer”.

Generally, Mia Huovilainen and Theodor Årnfelt have enjoyed the project more than they expected. Even though Mia Huovilainen thought building a robot would be very hard the first time she stepped into the lab, she now looks forward to exploring them further: “I’m thinking about writing my master’s thesis about robotics now!”