On Sunday September 11th, Swedish citizens will elect 349 members into parliament, called the Riksdag. Lundagård sat down to talk with Lars Edgren, Professor Emeritus at the Department of History, about the historical roots of Swedish democracy as well as the current election.

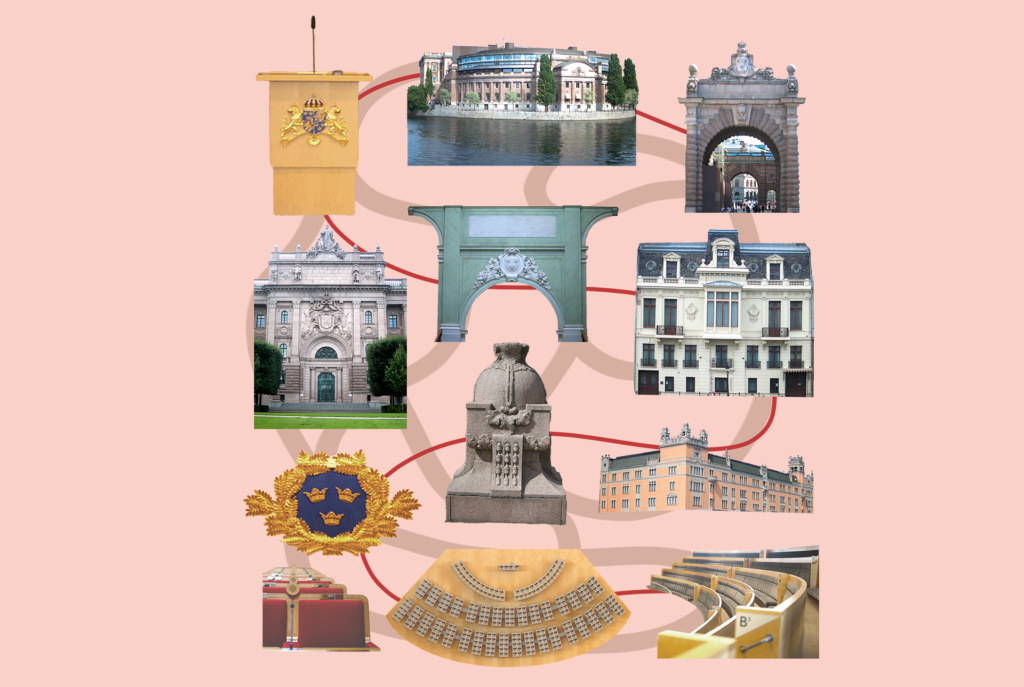

To understand the 2022 election, it seems best to begin at its origins. The term ‘Riksdag’ was first used in the 16th century, when king Gustav Vasa called for an assembly of the four estates. The estates, the nobility, the clergy, the burghers, and the peasantry, had only one single vote each.

Nonetheless, Lars Edgren, Professor Emeritus at the Department of History at Lund University, states that then “there was a potential for broader representation, especially since the farmers were represented, which is pretty unusual when you compare with other European countries at the time.”

An elite institution, exclusive to the enormously rich

By 1809, the Swedish constitution was established marking the division of power between the king and the Riksdag, and in 1865 the estate system was abolished and replaced by a two-chamber system, similar to current systems in for example Britain.

The first chamber was, in the words of Lars Edgren, “an elite institution, exclusive to the enormously rich”, whereas the second chamber “was a poor attempt at popular representation” – only male citizens above a certain income that owned land could vote and their vote was not democratic but weighted based on the amount of tax they paid.

This system was heavily criticised, and by the end of the 19th century several groups, including the feminist and socialist movements, were advocating for universal suffrage. Between 1907-1909, the first large reform took place; most men were able to vote, apart from those in debt, with a criminal record, on poor relief, or who evaded the compulsory military service.

World War I and the revolutionary fever that swept Europe expedited the process towards universal suffrage. Between 1919-1921, major reforms took place; the electorate was extensively widened, giving women and those with tax-debt the right to vote, and the king lost his political power.

Over the coming decades further restrictions were lifted. In 1975 the first chamber was abolished, the age of voting lowered to 18, and the 1809 constitution officially changed, introducing elections as they are now.

Voting Today

Lars Edgren attests that “the only restriction today in the right to vote in parliamentary elections is citizenship and age. This means that, for example, prison inmates and people with intellectual disabilities can vote. These are groups that were previously excluded [in Sweden, editor’s note], and are commonly excluded in [in other countries, editor’s note.] voting laws.”

The voting process has also been made as simple as possible; one can either vote at a polling station on the day or in advance. There is also an alternative to vote by proxy or, when living abroad, to send in your vote to the Swedish embassy. The votes are always for a party, and you have the choice of voting for a representative for that party as well. Parties with over four percent of the votes get represented in the Riksdag according to Sweden’s system of proportional representation.

Regional and municipal elections are held on the same day.

The Government

Sweden is governed by a majority parliament. The 349 seats in the Riksdag are dealt up between all parties according to the proportion of the vote they got, albeit with a four percent threshold to be eligible.

Once the Riksdag is elected, the house speaker proposes a prime minister. The Riksdag then votes on the prime minister, and if elected, the candidate is responsible for appointing ministers, thereby forming the government.

The government has executive power and is responsible for implementing the Riksdag’s decisions, it exercises limited legislative power as it proposes new laws, subject to the Riksdag’s approval.

If the government loses favour with the Riksdag it must resign. Usually, multiple parties within the Riksdag must cooperate to form a government. One single party seldom has an outright majority.

It is very difficult to predict what will happen

The Parties

In the last three elections, the same 8 parties have exceeded the 4 percent threshold and became a part of the Riksdag, but who are these 8 parties and how are they predicted to fare in the upcoming elections?

To the left on the political spectrum, the Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterna, S), Sweden’s oldest and largest party in the Riksdag, and the Left Party (Vänsterpartiet, V), with roots in the communist movement, seem set to get into parliament.

The Green Party (Miljöpartiet, MP) is however currently balancing on the four percentage threshold, to the bafflement of Lars Edgren: “For some reason, despite experiencing a climate crisis, people still don’t think environmental issues are the most important issues in the election.

Instead, Lars Edgren attests that “it seems that the electorate sees crime as the most important question at the election this fall”.

Despite formerly having “a rather great acceptance for immigration”, Lars Edgren reveals that public opinion changed severely after the influx of immigrants in 2015 and the coinciding spike in gang related criminality. This proved a catalyst for the right-wing Sweden Democrats (Sverige Demokraterna, SD), who according to Lars Edgren “have a long ideological continuity to Swedish ideals that bear at least family resemblance to fascism,” and continues to say that “they are an anti-immigration party” and that SD preach that Sweden’s open-door policy is at fault for the rising crime statistics.

Statistics from the Swedish Election Authority

As such Lars Edgren remarks that the entire Swedish political compass has shifted to the right and that “all the parties now must more or less say that they also want to be restrictive and also want to have tougher punishments”, with SD and the three other right-wing parties, the Moderates (Moderaterna, M), the Christian Democrats (Kristdemokraterna, KD), and the Liberals (Liberalerna, L), being at the forefront of these politics.

According to Lars Edgren it seems likely that all four of the right-wing parties (SD, M, KD and L) will make it into the Riksdag this year despite some initial difficulties for the Liberal party: “For some time it has looked very bad for the Liberal party, they only polled around 2.5 percent half a year ago. Then they changed their leader and their polling results rose.”

Finally, the Centre party (Centerpartiet, C) will likely have the decisive vote in the formation of a coalition government this year. Recently, they have supported the Social Democrats in the Riksdag as they refuse to work with the Swedish Democrats. However, they are also reluctant to cooperate with the Left Party due to their socialist politics.

Lars Edgren concludes that these elections will be “very exciting actually, very difficult to predict what will happen in the fall. In 2018, it took several months before a government was formed; we might get into a similar situation this year.”