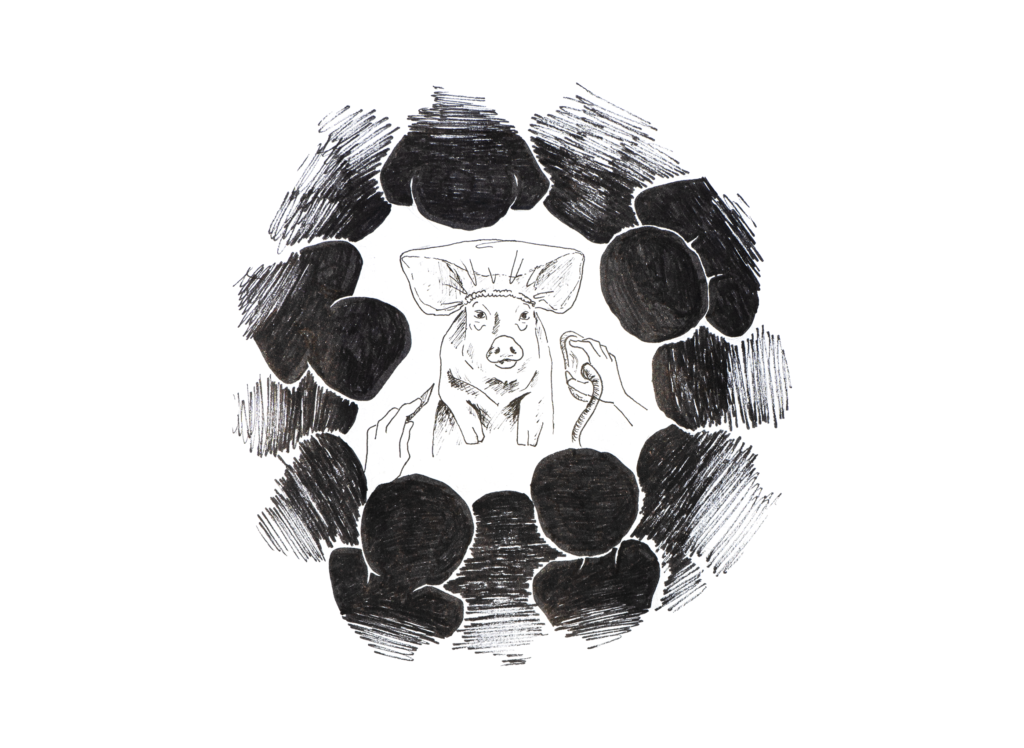

Forty live pigs are set to serve as educational material at Lund University (LU). The university’s use of live animals to train surgeons defies international trends and, possibly, animal welfare legislation. Why, then, has the university chosen not to discontinue the practice when there appear to be other alternatives?

This summer, the Malmö-Lund Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee granted Lund University’s application for ethical approval of a training element in upper gastrointestinal surgery, also known as upper GI surgery. The purpose of this element, the so-called “pig lab,” is to offer physicians undergoing specialty-training hands-on experience in performing surgical procedures by practicing on live pigs, which are later put down.

The university has been granted permission to perform these procedures on forty pigs within a five-year period. The purpose of the training element, which was performed on five pigs this fall, is to offer specializing physicians practical training in surgical techniques. According to LU, this objective cannot be achieved through alternative methods.

Internationally, however, an increasing number of highly-regarded surgical programs have discontinued the practice. Johns Hopkins University, home to one of the world’s most esteemed surgical programs, stopped using live animals to train surgeons in 2016. In conjunction with this decision, the university reported that an internal investigation had concluded that the experience “is not essential to the professional development of a medical student.”

Lundagård has been in contact with the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), an American non-profit organization with 175,000 members, 17,000 of whom are physicians. Per a report published by the organization, the use of animals for teaching at medical schools has been eliminated in the US and Canada.

Ryan Merkley is the Director of Research Advocacy at PCRM. He tells Lundagård that PCRM has not been able to identify any negative effects of eliminating the use of live animals from medical schools’ curricula.

“Research indicates that the shift has not had a negative effect on the educational development of surgical students,” Merkley writes in an email.

According to Merkley, American universities make use of other educational tools that better simulate the human body than animal models do.

Caroline Williamsson is a physician specialized in surgery and involved in course management for the upper GI surgery training at LU.

“In Sweden, a large share of upper GI surgeries are centralized to regional and university hospitals, meaning that many prospective surgeons in smaller cities lack access to necessary and continuous training,” Williamsson writes.

She also asserts that abroad, specializing physicians receive more training within the healthcare system itself since they get to assist in more operations. This is, Williamsson says, consequent of the fact that foreign surgeons generally operate more frequently.

“On an average day, Swedish surgeons spend more time on administration, reception, and investigations of patients who can be medicated than they do on operating. A surgeon-in-training in the US spends many more hours in the operating room than a Swedish surgeon does.”

According to Williamsson, alternative methods, such as the simulators mentioned by Merkley, do not suit the course offered by Lund University. Her stance is that no simulator is equivalent to the animal model in upper GI surgery.

Darius Barimani is a specializing physician who attended LU’s course in upper GI surgery two years ago. He chose to abstain from the pig lab.

“I don’t see why innocent animals should have to die for me to learn something about the human body.”

Even so, Barimani passed the course, suggesting that the course’s stated objectives can be achieved even without involving this component of training.

The greater part of the course was not improved by including practice on a live model, says Barimani.

“The only parts where practice on live animals is especially giving are liver hemorrhages and splenectomies. But if a student had only ever practiced on animals, they wouldn’t be able to perform that procedure independently on a human. They would have to wait for an on-call doctor who’s competent in that specialty.”

Students can just as well practice carrying out these procedures within the actual healthcare system, says Barimani.

“There is every opportunity to practice doing these procedures within the healthcare system instead, no matter what part of the country you live in. It would be better for all of us if specializing physicians were allowed to take advantage of that opportunity.”

He continues, telling Lundagård that he does not share in Williamssons opinion that the centralization of upper GI surgery is an obstacle to training within the system.

“It’s part of every specializing physician’s training to spend some months at a university hospital—so even those who don’t live close to a regional or university hospital have the opportunity to practice.”

Barimani also disagrees with the idea that too few operations are being carried out to allow specializing physicians to take part. It is chiefly a matter of these occasions not being offered as opportunities to practice, in his opinion.

“There’s a lot of room to practice procedures relevant to upper GI surgery, but it isn’t being utilized. As things are now, we specializing physicians mostly stand and watch during surgeries. The opportunity to practice could be increased even more if specializing physicians were allowed to participate more actively under the supervision of senior physicians,” says Barimani.

Svensk Kirurgisk Förening (SKF), or Swedish Surgical Association, also holds courses in upper GI surgery. This is to ensure that specialized competency training is available to more than the 27 students who can get spots at LU.

SKF’s courses are the most common training undergone by specializing physicians in upper GI surgery. In an email to Lundagård, SKF’s office relates that the association has chosen not to include the pig lab in their courses, mainly due to cost. Despite this, their program satisfies the same requirements that LU’s course in upper GI surgery does.

Daniel Rolke, an expert on animal testing at the Animal Rights Alliance, tells Lundagård that LU stands out among Swedish universities.

“Lund University in particular is very regressive regarding the switch to animal-free methods—they were, among other things, one of the last universities in Sweden to stop using cats for animal tests.”

Beyond the issue’s ethical dimensions, there is also the matter of legality. The Animal Welfare Act Chapter 7 Section 1 states that experimentation on animals can only be carried out if “the purpose of the activity cannot be attained by any other satisfactory method that does not use animals.”

The Animal Rights Alliance’s position holds that LU’s pig lab is irreconcilable with the Animal Welfare Act. Rolke also questions what the university actually intends to achieve with the activity.

“An entire continent has decided not to do the pig lab. Why can’t Lund University do the same?”

Williamsson stresses that the course held in Lund is a competency-based specialty training requested by the state, which is only offered at one school per year. This, in her opinion, means that it is not equivalent to the course offered by SKF.

She continues, confirming that SKF’s courses do indeed satisfy the same course objectives as Lund’s course, but adds that it “is of pretty low quality and many surgeons feel that they need more practical training than what is stipulated in the objectives.”

Regarding the question of the course’s relation to animal welfare laws, Williamsson refers to the committee on animal experimentation that approved the university’s application. “The ethical application was granted after having been tried against relevant legislation.”

The Animal Rights Alliance, however, is critical of using ethical clearance as a moral guarantor.

“Many of the people on that committee take part in animal experimentation themselves, and they grant just about every application they receive.”

The fall semester’s pig lab has been completed, and Lund University appears resolute in its decision to keep it in the curriculum. While surgeons in training do need hands-on practice, there appear to be several alternatives to using live animal models. Forsaking those alternatives, Lund’s approach brings further attention to some important questions: What role should live animals play in medical training? Should they at all be involved?

This article was originally published in Swedish in Lundagård issue 7 2021.

Translation: Sabina Rameke

In an earlier version of the article, the surgeons in training were referenced as ”medical students”. This has been changed.